This is something I get asked about from time-to-time… I know you don’t commonly see keyboard players using boards of effects pedals, like guitarists often do, but I have put a lot of thought into the setup I’m using on my gigs and I feel like this rig fits my workflow and my approach to my playing well.

I enjoy using tactile pedals to add or remove layers of sound ‘in the moment’, shaping the tone of my playing to fit the contours of the song; I have tried to build something which allows me to achieve a wide range of sounds on the fly, whilst keeping load-in and setup easy and convenient.

Check out the video for a full ‘rig rundown’ of the setup I’m using on my gigs at the moment.

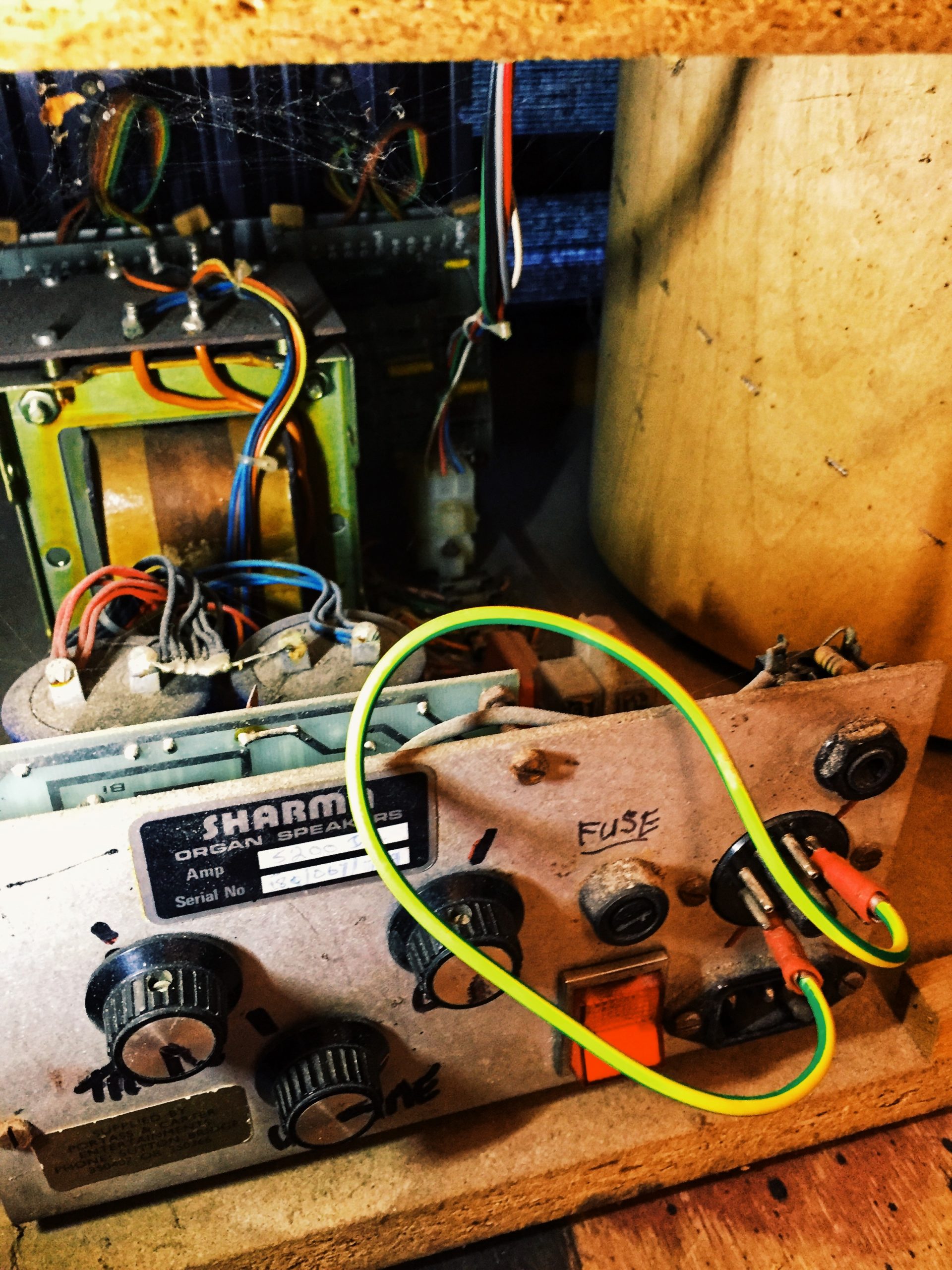

Click here for a full break-down on my custom rotary speaker speed-switcher pedal, as mentioned in the video.