In November I achieved a small dream of mine, as a keys player – I bought a genuine old vintage rotary cab for gigs and sessions where I’m mainly playing Hammond organ-type parts. My studio setup has evolved so that I try to stay away from emulators, and capture the sounds of real hardware and genuine components, wherever possible. So to be able to record and play live with a real rotary speaker for that sweet bluesy organ tone was a really exciting prospect for me.

The speaker I got is a Sharma 2000 – Sharma was a British firm which was a competitor to the famous American Leslie cabs during the ’60s and ’70s. It maybe a lesser-known brand, but the Sharma speaker still sounds just like the organ tone I’ve always wanted from my playing, and put a huge grin on my face from the first moment I sat down to play organ through it. (I’m playing it from my workhorse Nord Stage 2 keyboard setup as a B3 emulator – you can’t avoid emulators altogether! – but with the Nord’s built-in rotary function switched off.)

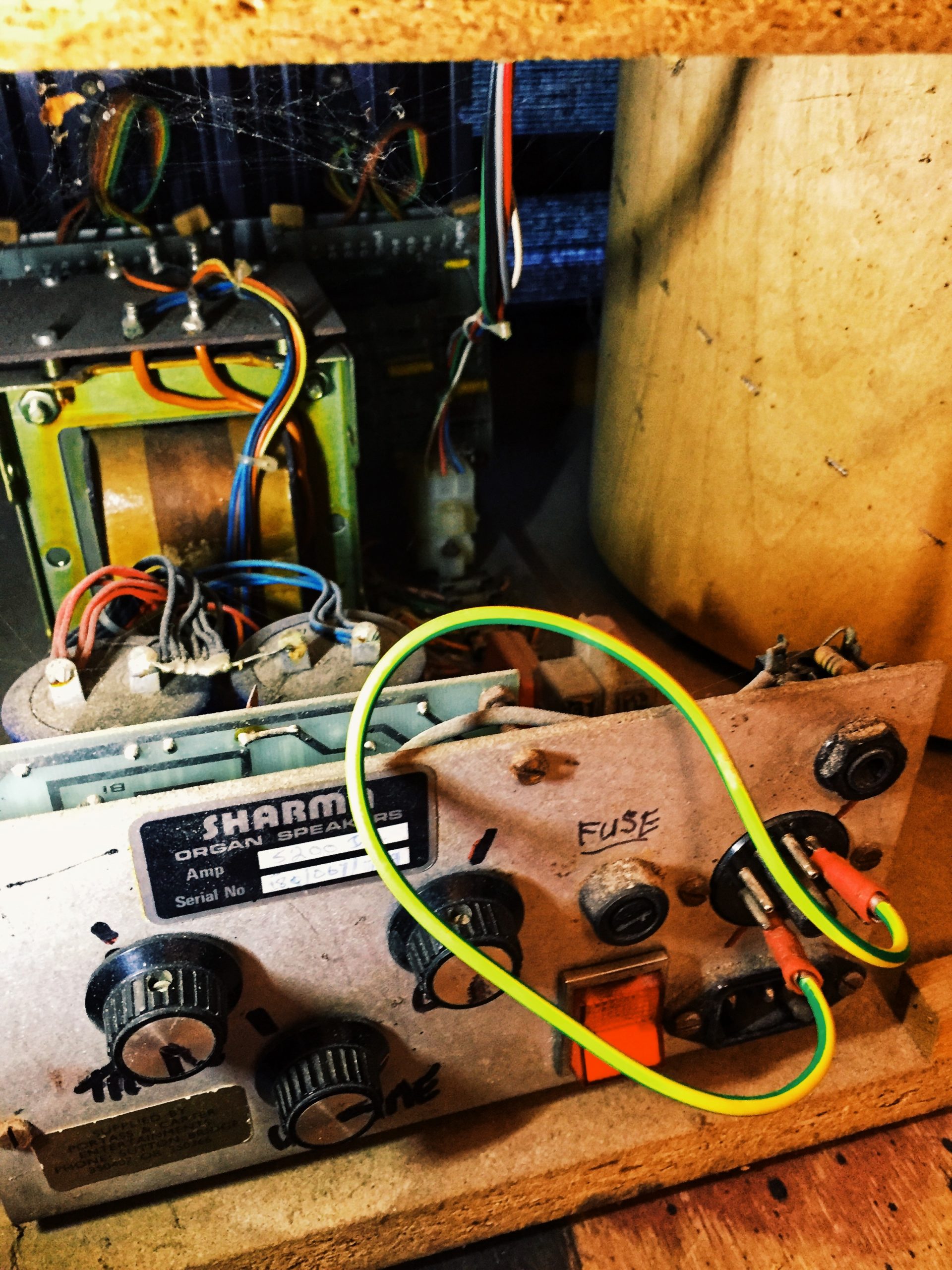

The Sharma speaker has the same 9-pin Amphenol connector you get on Leslies which carries input signal, volume information and various other program-change style controls. But unlike Leslies, the Sharma also has a ¼” jack line-level input and separate volume and bass/treble tone pots… So because the Nord Stage doesn’t have an Amphenol output (and the cables seem quite expensive!) I just used the line-level jack input and left the Amphenol well alone. Until I wanted to change the speed of the rotary motor inside…

When you use the rotary emulator in the Nord, you can switch from the slow setting to the fast with a latch pedal. I use a basic Yamaha sustain pedal (the FC5) for this, and I can just stamp on it each time I want to change the rotary speed. But that is plugged directly into the keyboard, so with only the line-level output going from the Nord to the Sharma speaker there was no way for that pedal to control the speed at which the physical motor inside the Sharma cab was spinning. So I thought I’d open up the Sharma 2000 and have a look around, to see how the speed of the motor could be controlled.

At this point, I wasn’t even sure whether you could change the speed of the motor at all; barring a skeletal Wikipedia article, I could find nothing about Sharma as a company online nor any documentation about any of their products – maybe, unlike Leslies, the Sharma rotary cabs had been built with only one possible motor speed? But I thought this unlikely, since they were designed to be competitors to Leslies, so I went exploring.

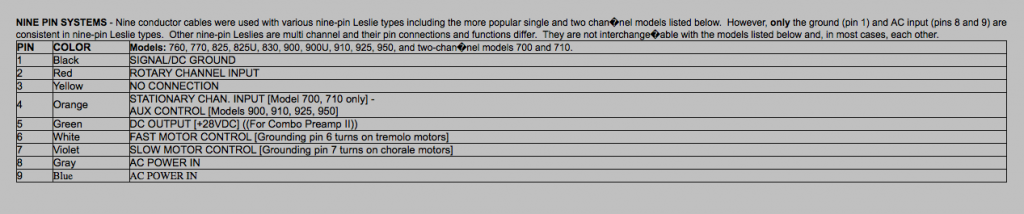

My first step was to find out more about the 9-pin Amphenol connectors, and what they could do. If it were possible to change the motor speed whilst the speaker was in use, it would be controlled from there – probably one of its pins carried information for rotary speed. Since the Sharma was designed to compete with Leslie cabs – for which there is a lot of documentation, not to mention a thriving online community, available – I went in search of a wiring pin diagram for Amphenol connectors used in Leslie cabs.

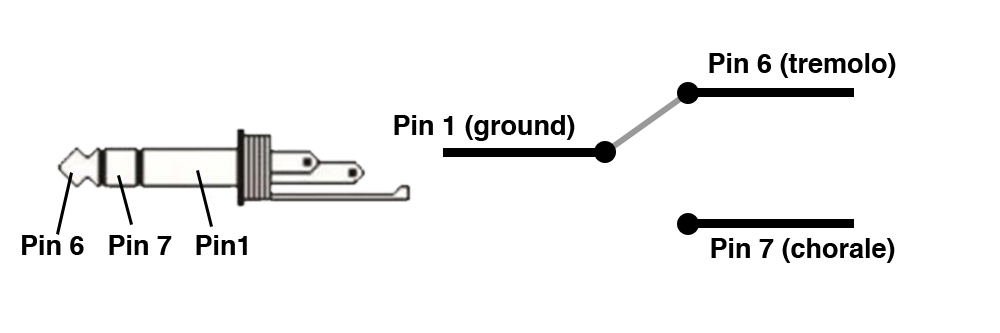

Typically for older engineering, it appeared that there was no standardised way to wire Amphenols for rotary speakers, and there were even variations in the numbers of pins used (some Leslie speakers being fitted with 5-pin, 6-pin, 11-pin or 12-pin versions of the connector instead) – but Uncle Harvey’s Guide To Leslie Pin-Outs proved invaluable, and I settled on a ‘most likely’ 9-pin configuration which suggested that grounding Pin 6 would result in a fast (‘tremolo’) rotary speed, whilst you grounded Pin 7 for the slow (‘chorale’) setting. The ground pin is Pin 1 – which explained why my Sharma had arrived with Pin 1 manually hardwired to Pin 6 with a small length of earth wire and a couple of cable crimps.

I ran a couple of quick tests, manually removing the cable crimped to Pin 6 and attaching it instead to Pin 7… And, success! The motor rotated slower, for the ‘chorale’ setting. I reattached the cable to Pin 6, and the motor sped up back to ‘tremolo’ speed. But I can’t get up from the keys mid-track, go round to the back of the speaker to fiddle with a little piece of wire every time I wanted to change the organ sound; now the challenge that remained was to be able to control this change from a footswitch whilst playing a song.

It was clear that I needed a pedal which could route a single source (ground) to one destination (Pin 6) to another (Pin 7) and back again. So unlike the momentary switching configuration of the Yamaha FC5 pedal I had been using to control the speed of the internal rotary emulator in my Nord Stage, this would need to be a single pole, double throw latching switch. Luckily this is the type of switch used in most standard guitar amp channel switching pedals – so I bought the cheapest generic guitar amp footswitch I could find which also had next-day delivery on Amazon, in the hopes of modifying it to suit my purpose in time to be able to use the Sharma 2000 (with a rotary speed switching pedal!) live on Sam Coe’s Comeback Queen album launch gig two days later.

My cheap generic footswitch (a ‘Neewer’-branded one with a pretty standard design) arrived the next day, and I opened it up to take a look at the wiring and see how I could adapt it to suit my needs. This pedal actually has two single pole, double throw switches wired to a ¼” TRS jack socket (one for each channel on a guitar amp), but I was only going to use one of the switches as I wanted to be able to stamp on the pedal in the same place all the time to change the speed without worrying about which switch was for ‘tremolo’ and which switch was for ‘chorale’. (A classic Hammond organ setup would utilise the second switch as the ‘brake’ function – ie. stopping the motor spinning altogether – but this wasn’t a priority for me as it’s not a function I use much in my playing, so I left it blank and focused on what I needed for the show in a couple of days’ time.)

As the Neewer pedal used a TRS jack socket to send its information – and came with a TRS jack-to-jack cable included – I needed another jack socket on the Sharma for the speed switcher input. Luckily I had some spare TRS sockets left over from another project, so I was able to just drill out a housing for it in the blank space on the panel at the rear of the cab next to where the other inputs and controls sit.

I re-soldered the wiring inside the pedal so that the single pole of switch number one was connected to the sleeve of the TRS socket, and the tip and ring were connected to one of each of the throws, then matched this on the TRS socket I had added to the panel on the rear of the Sharma speaker by soldering the sleeve to the earth wire crimped onto Pin 1, and removing the wiring the cables from the back of Pins 6 and 7 to solder one each to the tip and ring connectors, as per my wiring diagram below.

And all that was left to do was test it. See my YouTube video below for the full process and the final result!

And make sure to check out the video of Comeback Queen – the title track from Sam Coe’s debut solo album – live at Epic Studios in Norwich to hear the Sharma 2000 in action on a gig.

Leave a Reply